I was alone in Molly’s sterile hospital room. Covid restrictions prevented anyone else from being there. In the beginning, Jon and I could not be there at the same time or even switch off. I had to face the worst moments of my life (up to this point) without even my husband by my side.

I avoided talking to friends and family who were desperate for updates. I couldn’t bear their emotional reactions and questions. I wound up comforting them and quickly realized that I didn’t have it in me.

I didn’t like talking about Molly’s condition in front of her. I learned from my cancer experience that unconscious people hear what is said around them. During my twelve-hour bilateral mastectomy, I had an awareness of what happened around me. I couldn’t tell you what was said, just that my subconscious mind was active while I was under anesthesia. I’d been terrified of being “put under,” but after my mastectomy, that fear completely vanished. I’ve had several more major surgeries since then and looked forward to drifting off, secure in the knowledge that I – meaning my consciousness - would still be there, although I wouldn’t be able to feel the doctors opening my body. What a monumental realization that we humans are not our bodies! This knowledge would be important, as I grappled with what was happening to Molly.

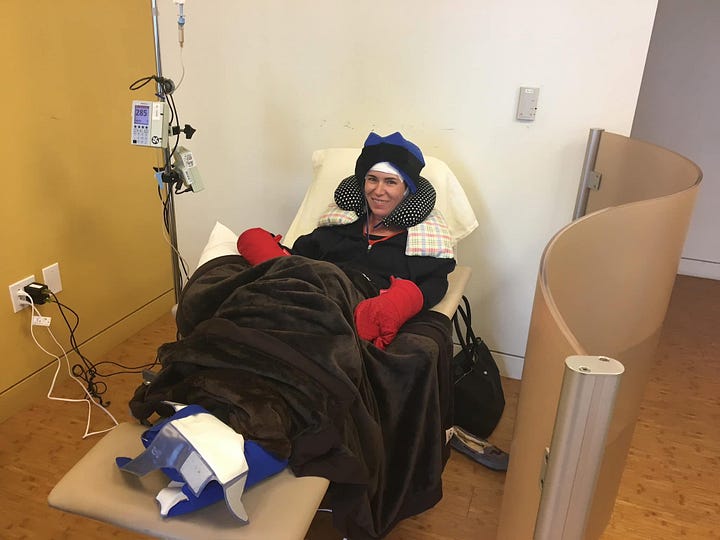

My friend, Leslie, who’d been by my side during chemo, came to the hospital every day. She’d park her Lexus SUV in front of the hospital, where we would sit and eat (which I wouldn’t have done nearly enough otherwise). You aren’t supposed to linger, but everyone likes Leslie. The attendant never rushed us. It was the only time I took my mask off. Jon and I wore masks even when we slept at the hospital. Our anxiety about Molly made it hard for us to breathe. It was no longer automatic. I had to remind myself to inhale and exhale (and still sometimes do, all this time later). The masks were suffocating. They obscured the faces of everyone at the hospital. I couldn’t remember who people were or read the subtleties of their expressions.

Besides Jon, Leslie and a few others, I didn’t want to talk to anyone and ignored most of the messages that were pouring in. I preferred communicating on social media. I could post a single update instead of recounting horrifying facts, over and over. My new Twitter “friends” brought me comfort. I didn’t realize until much later that hundreds of thousands of people were following along. I hadn’t used the site much and knew little about it.

On my second night sleeping on the little couch behind Molly’s hospital bed, with all the anxiety-inducing sounds emitting from the cold metal equipment that was hooked up to Molly, I texted Jon, “I love you.” He replied, “I love you too. We will get through this. And so will Molly.”

The hospital eventually announced that Covid infections had sufficiently declined and two parents would be allowed in the PICU. At first, we weren’t allowed to be in Molly’s room at the same time but could trade off. Jon and I would take turns sleeping at the hospital. We’d eventually reach a breaking point and need to recharge. Neither of us wanted to leave Molly.

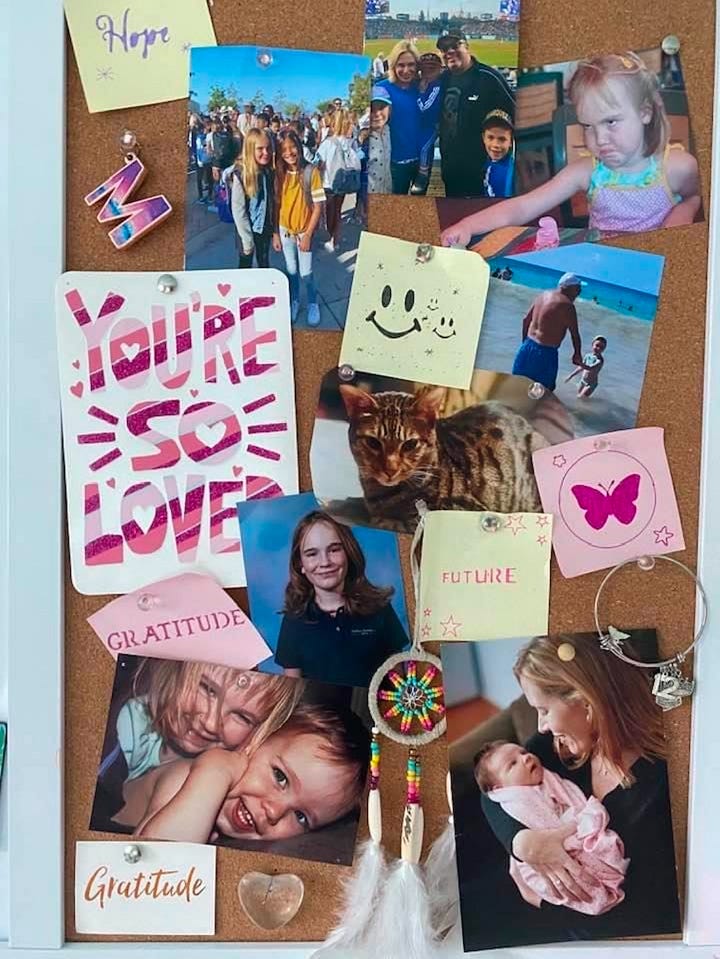

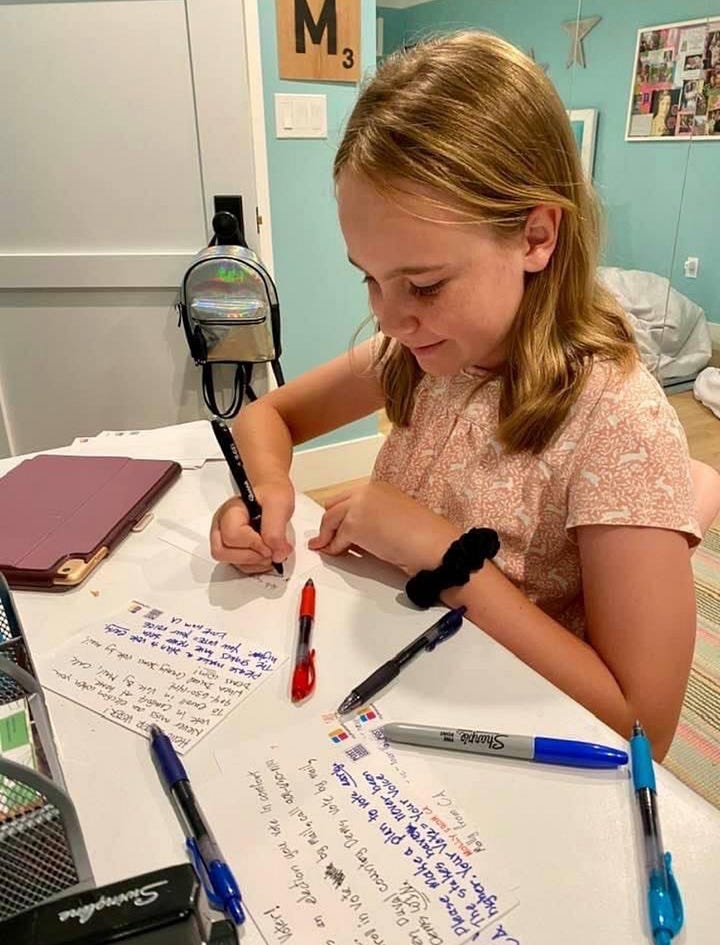

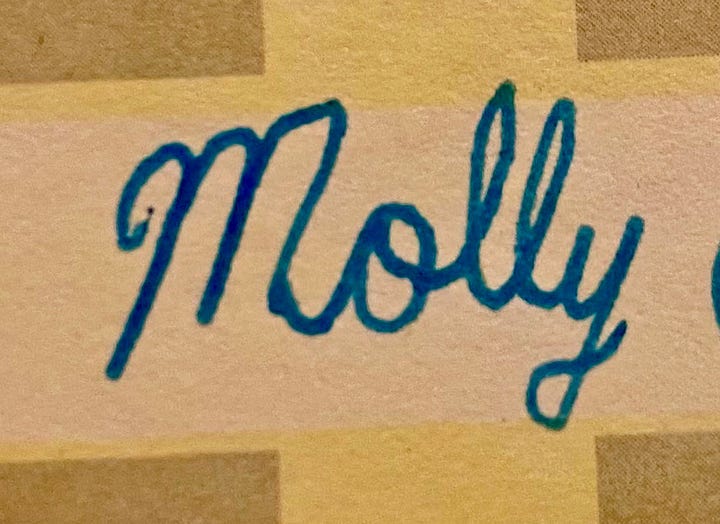

Back at our silent house, I sat in Molly’s room with my forehead on her desk. In the new pink desk chair she loved. She’d been practicing her signature in cursive, Molly Olivia, written over and over in different shades from her treasured collection of gel pens. The bulletin board over her desk contained words like “FUTURE” and “GRATEFUL” that she’d stenciled on post-it notes, next to drawings of hearts and butterflies. Just a few months earlier, Molly had been excited to paint her bedroom walls a cheerful shade of blue, similar to her turquoise bike helmet.

My shoulders shook as I heaved giant sobs. I wanted Molly to wake up and to prepare for her to come home. I wanted to turn back time to just two days earlier, when she’d been FINE. If only there’d been Sunday school like every other week! If only Mel hadn’t texted me about the girls riding the bike. If only I hadn’t said yes. If only they hadn’t wanted to go. If only I had realized the bike wasn’t a normal bike. If only, if only, if only. If just one thing had been different.

Eli had joined Nate at Jon’s parents’ house. Our rambunctious Weimaraner puppy, Calvin, was staying with his trainer. Leroy, our moody spotted cat, was the only source of company in our normally bustling, now excruciatingly quiet, home. Our community, desperate to help, offered to send food. I suggested alcohol. Jon and I had no appetites. We consumed the minimum necessary to keep our bodies going. We both became noticeably thinner.

The attending doctor on duty during our first week at the hospital was Dr. Irwin Weiss, a tall man in his mid-to-late fifties who wore a yarmulke. He did not have a warm bedside manner. Each morning, the doctors, nurses and medical students would conduct rounds. I didn’t like hearing Molly treated like a case study. They talked like we weren’t there, living our worst nightmare right before their eyes.

The morning after the accident, Dr. Weiss said he was optimistic that Molly would fully recover, with the caveat that he “didn’t know everything,” including how long it would take. He said to think of her recovery in terms of weeks, possibly months.

That afternoon, Dr. Weiss ordered one of the heavy sedatives to be lifted for an hour to see if Molly would wake up. We called her name and tried to rouse her. Nothing. I thought Molly would open her eyes, and it gutted me when she didn’t. Dr. Weiss said it was not unusual a day after brain surgery, and that he was increasing sedation again to allow Molly’s brain to rest and decompress as much as possible. One of the nurses asked us not to talk so much to Molly in order to keep her brain activity low. That was hard. I wanted to keep telling her I was there, that she was going to be ok, how much I love her.

I told Dr. Weiss I was scared Molly would not wake up. He said he was “fairly certain” she would. His equivocation made my stomach drop and my face grow hot. As lawyers, Jon and I are trained to pay close attention to words. I pressed Dr. Weiss to explain what he meant. He said he didn’t see any reason why she wouldn’t wake up but reminded me he isn’t God (as if I thought he might be). He said her EEG showed brain activity. Since he brought up God, and his yarmulke suggested he was religious, I asked Dr. Weiss to pray for Molly. He displayed no emotion but fished a small notebook out of his inner lab coat pocket and jotted down her Hebrew name, Miri Hannah bat Chava v Rachmiel.

My Hebrew name is Chava. I chose it for myself when I converted to Judaism. Chava means “life” in Yiddish and “Eve” in Hebrew. Jon’s is Rachmiel. “Bat” means daughter. Miri Hannah daughter of Chava and Rachmiel. Molly Olivia, daughter of Kaye and Jonathan. This is how we refer to our daughter in prayer, and how other Jews pray for her. Miri Hannah - Molly Olivia - has been lifted up in prayer by hundreds of thousands of people throughout the world. Jon and I constantly prayed and bargained with God. There was little else we could do.

I often read to Molly in the hospital. I’ve read aloud to our kids nearly every night since they were born. Molly’s language arts class at school had recently started reading George Orwell’s “Animal Farm.” Molly was passionate about animal rights and fascinated by the workings of government. She excitedly told me about the book. She liked that it contained a character named Mollie, a silly horse who “focused on things that weren’t important.” She was glad their names were spelled differently. I read “Animal Farm” to her in the hospital, asking her what she thought about certain scenes and characters, desperately wishing she could respond. I enjoyed seeing the passages Molly chose to highlight and wondered what made them stand out to her. She was so bright. Molly would have had such interesting observations, things that didn’t occur to others.

When I saw the dreaded Dr. Weiss again, I said I’d been agonizing over him being “fairly certain” Molly would wake up. He seemed surprised, like he’d forgotten he said it. He confidently said, “Oh, she’ll wake up. I mean, the building could fall down and kill us all, but unless something like that happens, she will wake up.” Dr. Weiss said it could take weeks, and they didn’t know if she would be herself or have limitations. Her CT scan showed improvement over a previous scan, which was encouraging. None of them showed brain damage. We were cautioned that CT scans do not show the full picture. An MRI, to be performed later, would tell us more. The assurance that Molly would live enabled me to continue putting one foot in front of the other. I didn’t care what I had to go through, or what her recovery would entail. I was desperate for Molly to wake up. We knew was strong and determined. She would never want to leave us.

Late that afternoon, my father texted and asked for an update on Molly. Word of the accident must have reached him through a relative who saw my social media posts. Our relationship has been strained (mostly non-existent) most of my adult life, although we used to be close. I’m his only child. He met Molly a handful of times when she was very young. I’d asked him to come and see me during cancer treatment but he never did. He didn’t attend our wedding, so this wasn’t shocking. It still hurt when I was so sick. After my dad remarried, his wife and her kids became his family. I was an unwelcome reminder of his past that didn’t have a place with them.

I didn’t react kindly to my dad. I replied, “My first instinct was to call you and cry and hope you could say something to comfort me. In a crisis, you want your parents. Unfortunately, I have not had that. Molly is 12 years old and you have made no effort to be part of her precious life. And it caused her pain. She has brought it up with me several times that it makes her sad that she has a grandpa she doesn’t remember and doesn’t know. So I don’t think you should be worried about her now.” I included two photos of bald Molly, intubated, lying in a hospital bed, tiny amidst all the equipment that surrounded her. I wrote, “This is how she is.”

I was filled with anger. At him for abandoning us. At God. At the whole damn world.

Molly didn’t remember my dad. She was saddened by the thought that she had a grandfather whom she didn’t know, and it upset her that neither of my parents had ever seen Eli. During a walk around our neighborhood a few weeks before the accident, she asked why she never saw my parents. I explained, as gently as I could, that my mom was sick and unwilling to accept our offers of help. A few months before my mom’s father died in 2016, she left his house, where she’d been living, saying she’d rather be homeless than continue living with her family. She, in fact, did in fact live on the streets for years. There was nothing we could do. We didn’t know where she was or how to reach her. After I was diagnosed with cancer, I stopped searching for my mom, knowing I needed to focus all my energy on surviving. She’d always brought chaos into my life and there was no more room for it.

I went home that night and Jon stayed at the hospital with Molly. When I’d reach a point of uncontrollable crying at the hospital, I knew I needed to step away. I wanted positive energy around Molly. I’d drive home in my black Honda minivan - on the 10 freeway and the Pacific Coast Highway - barely able to see through my tears. I pleaded out loud, “Molly, Molly, Molly. PLEASE! I need my girl. I need my girl. I need her. Please don’t take my girl.” I had to pull to the side of the road and wait until enough of the pain was released before I could make my way home. It took a long time.

More recently, we found my mom and even bought a home in Arkansas (where she’d decided to move) for her to live in. I still haven’t seen her in over eight years. She stayed in the Arkansas house for a few months before returning to the streets. I heard she turned up in my hometown of Fresno, California, around the holidays. I think she’s staying with her ex-husband, who’s been bedridden for years. My poor sisters and niece. Many people carry so much pain that is invisible to the outside world. Looking at them, you wouldn’t imagine what they’ve endured.

I heard from my dad when the Palisades fire broke out. I appreciated it. We had some nice text exchanges but haven’t spoken. Life is fragile and short. I want to forget all the bad things that have happened between me and my parents. And everyone else, really. I want to live in the present moment - really LIVE. I imagine myself dropping the enormously heavy load of pain accumulated over the past 47 years and leaving it all behind. We’re all human, trying, falling short, working with what we’ve got. Constantly evolving. I try to focus on what matters most, what I want to accomplish with my limited time left on Earth, knowing it could be over at any moment. Sometimes I miss the mark and get caught up in nonsense. Then I refocus.

This is why I’m sharing these writings. In the aftermath of Molly’s death, literary agents who followed my social media posts reached out. Sheryl Sandberg offered help in telling our story, generously offering to write the forward of my future book. I’ve known my entire life - long before any of this happened - that I would write a book. I was in such a state of shock during the first year that I could only pour my feelings onto pages and pages of notebooks from Molly’s desk. Spiral bound notebooks she should have been filling with sixth grade homework.

I’ve been working on my book, on and off. There’s so much to say. None of it’s easy. The subject matter is heavy (not something you can dabble in, then head off to lunch with a friend). It’s also physically challenging for me to work at a computer because my hand sustained permanent nerve damage when cancer consumed the lymph nodes under my arm.

I’m raising traumatized boys (now 8 and 14) who are incredible but have been through too much in their short lives. They need me. My community needs me now, in the wake of a devastating fire. I’m a doer. A helper. Imperfectly human but showing up, fighting the good fight.

My book will have to wait for publication. My story is still unfolding. But I’m not taking chances, knowing full well that today could be my last. The story you are reading isn’t edited. It’s not polished. It does, however, need to be told. I’m putting it into the Universe, trusting it will reach someone who needs to hear it. Knowing that Molly is guiding me.

To be continued . . . .

Thank you for continuing to share Kaye. 🙏 Not only do I “see” your pain through your words, I feel your grief along with you & have since Molly’s accident & seeing your outcry for prayers, if that’s even possible to understand. I remember much of those terrifying days; other things are my 1st time reading. The video of Molly outside Eli’s room is gut wrenching; I’m so sorry; my heart breaks for you and Jon. 😢💔 I love the photo of Molly in her room, deep in thought and wonder what it was she was thinking about.

I’m 💯 certain that you’ll finish your book & that it’ll be a bestseller; after all, as you said, Molly’s guiding you! I have to say that as a future reader, I don’t think it needs much editing or polishing. I like that it’s raw, your deepest feelings straight from your heart.

While I wish with all my heart the accident never happened, I’m grateful that I stumbled upon your post and to you; you are truly an inspiration and the world is better with you in it. Love, Mary 🙏❤️💜💫 #TEAMMOLLY